The Blockchain Debate Podcast

The Blockchain Debate Podcast

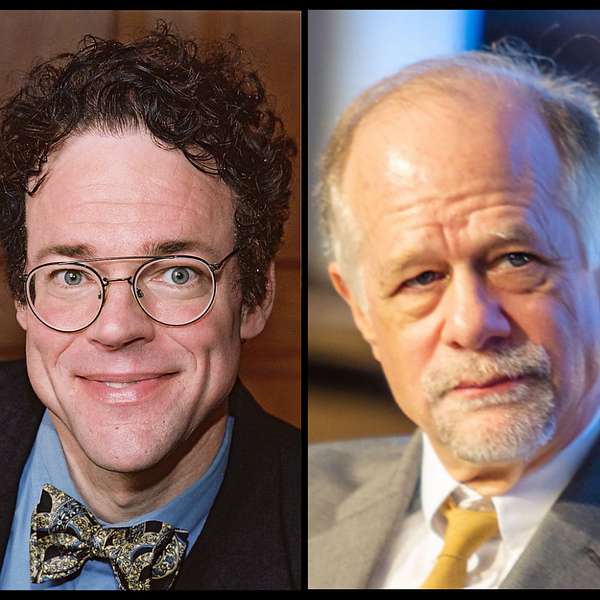

Motion: The US urgently needs to catch up on Central Bank Digital Currency (Robert Hockett vs. Lawrence White)

Guests:

Bob Hockett (twitter.com/rch371)

Larry White (twitter.com/lawrencehwhite1)

Host:

Richard Yan (twitter.com/gentso09)

Today’s motion is “The US urgently needs to catch up on CBDC.”

Central Bank Digital Currencies are sort of like government-run Paypal accounts. They allow the government to do scalpel-like fiscal policies more easily, such as airdropping cash to citizens and stimulating spending.

At the same time, CBDC could also allow the government to track individual spending behaviors.

China is obviously leading the effort in CBDC adoption for all major countries. As of recording time, it’s already run multiple trials in various major cities. This has spurred a debate as to whether the US should follow suit.

We discussed:

* CBDC and privacy

* The consensus from the right and the left on the importance of CBDC, but the lack of urgency for implementation

* Countries adopting Bitcoin as a legal tender

* Hype vs reality: The possibility of China's CBDC becoming a currency to settle international trade and therefore be a real threat to USD

* CBDC's potential cannibalization of private banks

If you would like to debate or want to nominate someone, please DM me at @blockdebate on Twitter.

Please note that nothing in our podcast should be construed as financial advice.

Source of select items discussed in the debate (and supplemental material):

- Bob's article explaining his position: https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/497427-americas-digital-sputnik-moment

- Larry's article explaining his position: https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/spring/summer-2021/should-state-or-market-provide-digital-currency

Guest bios:

Bob Hockett is a professor at Cornell Law School, focusing on Corporate Law and Financial Regulation. He is a fellow of the Century Foundation and a regular commissioned author for the New America Foundation. Bob also does regular consulting work for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the International Monetary Fund, Americans for Financial Reform, the 'Occupy' Cooperative, and a number of federal and state legislators and local governments. He is the author of the book “Financing the Green New Deal: A Plan of Action and Renewal.”

Larry White is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. He is also a professor of economics at George Mason University. He has written five books on banking and monetary policy, including The Clash of Economic Ideas, The Theory of Monetary Institutions, and Free Banking in Britain. He is editor and co-editor of various publications, including Renewing the Search for a Monetary Constitution and The History of Gold and Silver. He also writes regularly for the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives publication called Alt‐M.

CBDC Debate

INTRO

Richard: [00:00:00] Welcome to another episode of The Blockchain Debate Podcast, where "Consensus is optional, but proof of thought is required." I'm your host Richard Yan. Today's motion is "The US urgently needs to catch up on Central Bank Digital Currency."

[00:00:22] Central Bank Digital Currencies or CBDC are sort of like government-run PayPal accounts. They allow the government to do scalpel-precision fiscal policies more easily, such as airdropping cash to citizens and stimulating spending. At the same time, CBDC could also allow the government to track individual spending behaviors, which can be a concern for privacy. China is obviously the front runner in leading the effort in CBDC adoption amongst major countries. As of recording time, it's already run multiple trials in various major cities for its CBDC project. This has spurred a debate as to whether the US should follow suit.

[00:01:01] The two debaters today are two professors who also have experience working for American think tanks and advising American policymakers. Many debates about CBDC devolve into statist versus libertarian discussions. But I'm glad to say that today's debate started from a place of common understanding and not from ideological extremes. Towards the end of the debate, when the guests discussed whether the Fed will cannibalize the business of private commercial banks, we got a bit sidetracked about Fed policies. So just be forewarned.

[00:01:33] The speakers also talked about their reaction to El Salvador adopting Bitcoin. Because this was recorded before the official passage of the bill in El Salvador, there was some outdated information in the discussion. For instance, the bill will allow payment of USD obligations in Bitcoin, but the speakers didn't know about this at the time of recording.

[00:01:54] If you're into crypto and like to hear two sides of the story, be sure to also check out our previous episodes. We feature some of the best known thinkers in the crypto space. If you'd like to debate or want to nominate someone, please DM me @BlockDebate on Twitter. Please note that nothing in our podcast should be construed as financial advice. I hope you enjoy listening to this debate. Let's dive right in.

DEBATE

Richard: [00:02:14] Welcome to the debate! Consensus optional, proof of thought required. I'm your host Richard Yan. Today's motion: The US urgently needs to catch up on Central Bank Digital Currency.

[00:02:25] To my metaphorical left is Bob Hockett arguing for the motion. He agrees that the US urgently needs to catch up on CBDC. To my metaphorical right is Larry White arguing against the motion. He disagrees that the US urgently needs to catch up on CBDC.

Guest Bios

Richard: [00:02:39] Let's quickly go through the bio's of our guests. Bob Hockett is a professor at Cornell Law School, focusing on Corporate Law and Financial Regulation. He is a fellow of the Century Foundation and a regular commissioned author for the New America Foundation. Bob also does regular consulting work for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the International Monetary Fund, Americans for Financial Reform, the 'Occupy' Cooperative, and a number of federal and state legislators and local governments. He is the au

[00:03:09] Larry White is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. He is also a professor of economics at George Mason University. He has written five books on banking and monetary policy, including the "The Clash of Economic Ideas", "The Theory of Monetary Institutions", and "Free Banking in Britain." He is editor and co-editor of various publications, including "Renewing the Search for a Monetary Constitution" and "The History of Gold and Silver." He also writes regul

[00:03:40]Bob: [00:03:40] Hey! Thanks so much.

[00:03:41] Larry: [00:03:41] Good to be here.

[00:03:42] Richard: [00:03:42] Great. So we normally have three rounds. Opening statements, host questions and audience questions. Currently our Twitter poll shows that most agree with the motion that the US needs to catch up with the CBDC action. After the release of this recording, we will also have a post debate poll. Between the two posts, the debator with a bigger change in percentage votes in his or her favor wins the debate.

Bob's Opening Statement

Richard: Let's get started with the opening statement. Bob, could you please get started and tell us why you think the US urgently needs to catch up on CBDC?

[00:04:13]Bob: [00:04:13] You bet. Thanks Richard. And again, great to be on with Larry and for your honor, in fact. My approval of the motion is basically predicated on the following couple of observations. The first is, if we talk about CBDC in terms of digitality rather than in terms of any particular hardware, like blockchain technology or distributed ledger technology and the like, it's a lot easier to be in favor. In other words, I don't want what I'm about to say to be construed as meaning that I'm all gung ho about blockchain, or distributed ledger, or any other particular underlying technology. Although of course, some technologies currently in development lend themselves more immediately or efficiently to a kind of universal digital payments platform better than others do, but again, I don't want to be taken to be wedded to any particular hardware.

[00:04:58]The second maybe preliminary point to make, is that just so you know, it'll maybe avoid certain possible confusions. When I think in terms of a currency, I think in terms of an entire payment system. Indeed I think one helpful definition or understanding of money would be simply as that which pays in a payment system or practice of payments within a given society. In other words, money presupposes some kind of an exchange economy, some form of exchange that occurs. Exchange in turn can occur by monetary means or by barter. It occurs by monetary means in effect what we're doing is recognizing some things as counting quote-unquote for purposes of discharging obligations, that one incurs when one takes or receives goods or services from somebody else. Money, therefore in that sense could be considered to be simply that which pays or that which counts in a system or practice of paying, and which counts in a system of value accounting. That's the sort of background understanding that I'll be proceeding from. Now given that, the question of whether we urgently need to catch up when it comes to CBDC development, can be slightly reformulated and that is, do we urgently need to update our payments system? In particular, do we need to update our payment system in a manner that involves the Federal Reserve here in the US and other Central Banks elsewhere in other jurisdictions? Here in the US of course it would be the Fed and I think here the answer is pretty clearly, yes.

[00:06:24] Interestingly enough, I think even though I agree with something that I believe Larry is going to say, which is that the primary locus or site of innovation when it comes to new payment systems, new payment technologies, new payment platforms, new payment methodologies is indeed the private sector. I think not withstanding the fact that the private sector is the locus where most of this kind of innovation occurs, that it's part of the ordinary trajectory of financial development and monetary development over time for new systems or new modes to be developed in the private sector or some mode ultimately to emerge as superior, at least for some period of time and for that system then in effect to be adopted wholesale by the polity at large, and to be universally provided.

[00:07:08] Now, I think we're at that point basically when it comes to digital payments technologies. Basically I think we're at a point where it makes sense to have a single national platform, single national digital payments platform, equally available to all individuals and businesses, small and large alike. The currency that would be used or that would be transferred over a system like that, just would be the CBDC in question. In effect, here in the US that would be a digital dollar. Now, a couple of quick final points before I stop for just a moment, at least. Why do I think that would be a good idea? What do I think about the advantages of basically offering every individual and every small business, every business, actually, for that matter in the US a Fed provided digital wallet, with of course a corresponding digital dollar as the currency essentially the medium of exchange and the unit of account on that platform?

[00:08:00]I think there are a number of particular benefits that deserve highlighting, right? The first has to do with just basic commercial and financial inclusion. We know that it's difficult for various reasons, sometimes owing to market failure reasons, other times owing to other reasons, for sizable numbers of our population not to have access, at least not affordable access to payment technologies or payment platforms on the one hand and savings platforms, basically value storage platforms on the other. That's a sort of a long-winded way of saying we know that there's a problem with the unbanked. We also know that while the FBI see estimates that the unbanked population or under-banked population amounts to something like 25% of the adult population, the un-smartphoned population is only about 5%. If there were a platform that was available to all over their smartphones or other comparable devices, rather than just in brick and mortar form, we could pretty quickly in a single stroke afford a kind of universal banking or savings and payment transfer platform to everybody. So the interest of financial inclusion and commercial inclusion, it seems to me is met by something like this.

[00:09:06] It also strikes me there's a side point in this connection. That in a society that considers itself a commercial society, or in an economy that considers, whose members consider it an exchange economy, the means of exchange or the means of commerce, the payment platform, can be considered a fundamental or a basic infrastructure, right? A basic public utility that's presupposed by an equitably available commercial society or equitably available exchange economy. That's so much for inclusion and universality.

[00:09:35] There's, in addition, I think a growth and efficiency argument to be made here. That is that basically just as a matter of straightforward scale economies, right? If you have a single payment platform that's available to everybody so that you don't have to worry about problems of intertranslatability or interfacing between distinct payment platforms, you have all else being equal, a much more efficient network technology or a network platform that everybody can use, and if you can facilitate much more rapid clearing and settling the transactions much more rapid transacting like that, that's of course an efficiency gain in its own, right? It also can be considered all else being equal a growth gain because as we measure economic growth in terms of transaction volume, and so if you're increasing transaction speed, then all else being equal and of course, in a given time interval, you're increasing transaction volume. Thereby increasing growth by the measure or the metric that we use in measuring it.

[00:10:35] Third, we can enjoy a kind of leak proof monetary policy with a platform like this. Currently the way Fed monetary policy works is via the medium of private sector banking institutions. Sometimes that medium serves us well and enables the Fed quickly to clamp down on credit money availability or quickly to expand credit money availability, but other times it doesn't work so well, and you get the so-called pushing on a string problem, for example, of the kind that was quite conspicuous in 2009, 2010. If everybody had a digital wallet that the Fed could make payments into and take payments out of, or through which the Fed operated and cut out the middle men as it were of the banking sector, you would have again, a more leak-proof method or mode of monetary policy transmission and conducting.

[00:11:25]In addition to that or sort of in that connection, you could even imagine interest being paid on Fed digital wallets. A kind of personal counterpart to the IOR that Fed now pays out to the privileged banking and other financial institutions that have sole access to Fed accounts or Fed banking accounts. Then of course you could use the interest rates offered on those particular wallets as a very effective or potentially very effective monetary policy tool. Raising rates when you're trying to encourage more saving, lowering rates when you're trying to encourage more spending.

[00:11:58] Fourth, there's of course a privacy advantage. At least if we're talking about electronic payments and electronic saving and because of course the technologies that are out there render encryption of transactions quite easy, quite straight forward to do. Furthermore, if this were administered by the Fed, you don't have an entity that has a private profit motive to undercut or to hedge around that line of encryption that doesn't have an incentive to harvest quote unquote commercial data or financial data than to sell to vendors, and so on. And you see, Sweden is effectively capitalizing on this very prospect in the e-krona project where basically transactions up to a certain amount are default encrypted and it's only once they cross a certain threshold, basically the same threshold that we have when it comes to bank secrecy laws, that the encryption where at least the encryption is lowered. I guess you could say the threshold is lowered and, public scrutiny or public sector scrutiny is allowed to look out for terrorist finance or money laundering or what have you.

[00:12:57] And then finally, fifthly, this will be the final point, is there are certain kinds of public good that certain people commonly provide that are very difficult to compensate at the moment, and so they remain under-provided public goods. Certain kinds of care work, for example, like older kids tutoring younger kids after school to do their mathematics homework or their whatever other kinds of homework they might have help with. Or folk who kind of looking on shut-ins or take care of grandparents or great-grandparents or what have you. A lot of these sorts of goods that are provided are very difficult of course to verify their provision of currently and hence for the public to make any serious effort at compensating in order to encourage more provision of which then of course yields greater growth benefits. But the technologies that are emerging now that are associated with digital currencies with proof of work with quick transferability of credits over the accounts that are over the networks in question, enable at least the beginnings of public compensation of certain kinds of care work that are themselves public goods, which in the longterm benefit the public fisc. So that's a kind of a marginal additional benefit. I wouldn't want to hang my head entirely on it, but it seems to me that it's more than negligible at this point and I would close this opening set of remarks with that fifth sort of advantage or with recognition of that fifth advantage that doing something like this would allow us to do.

Larry's opening statement

[00:14:20] Richard: [00:14:20] Okay. Sounds good, Bob, all very sensible and not totally surprising as you're in the sort of majority position So I'm very curious to hear what Larry has to say to all of that. Larry, go ahead with your opening statement. Why do you think the US does not need to urgently catch up on CBDC?

[00:14:38] Larry: [00:14:38] Thanks. There are a lot of different proposals that are being floated under the rubric of CBDC and they would operate in different ways. And Bob said he didn't want to be pinned down to any particular way of implementing it. But we have to be specific if we're going to try to tote up costs and benefits, and there's a basic distinction between two different models. What's been called the Fedcoin Model, which would provide Bitcoin like pseudonymity to users. Those kinds of proposals are not getting much traction politically and the treasury has already formerly proposed to ban self-hosted cryptocurrency wallets on the grounds that there are too similar to anonymous bank accounts. That is, they allow too much privacy. The more popular set of proposals have been called the Fed Account Model, where as Bob said, every person, every business, except perhaps the undocumented, what to do with them is a problem in this system, can have account balances directly on the Fed's balance sheet, so the Fed is providing a retail digital dollar system.

[00:15:46] Now, we've already got a retail digital dollar system. Most payable dollars held by the public in ordinary checking account balances, they're already digital. They're already intangible, and they can be sent down wires or sent through the internet, so new information technology doesn't change that. What it does is to speed up deposit transfer and settlement, and to make it more convenient to send and to receive, and those developments have happened in the private sector, so right now you can send money from one customer in one bank to a customer and another bank via the Zelle service, which is operated by a consortium of US banks, and the money is available to the recipient in minutes. Venmo now accepts direct deposit of paychecks and makes the money available to the recipient just as quickly. We've got Cash App, we've got Apple Pay, we've got other phone apps for convenient digital dollar payments. So the question then is why do we need the Fed, either the Federal Government or the Federal Reserve, to enter the retail payment space? Often the advocates of CBDC, and I think Bob to some extent, have other policy goals that they want to wrap up in CBDC to give them more tech appeal. So Bob mentioned financial inclusion, other people have mentioned a guaranteed basic income, Bob mentioned doing monetary policy by direct injection of money - I think there are better ways to pursue those goals.

[00:17:17] To ensure that everybody has access to food, the Federal Government doesn't need to operate supermarkets, right? It issues so-called food stamps. To give people more internet access or phone service, we don't need a federal internet service or a government phone company. We do those things through the private sector. So what are the advantages of private sector provision? By contrast to the Fed, private sector providers, banks, and other financial firms, have to compete for customers and give people better options to attract them. Competition selects for the kind of features people want in payment projects. If it doesn't attract enough people to pay costs covering prices, it doesn't survive. But to survive, it doesn't need to satisfy everybody, it doesn't require one size to fit all. We don't put all our eggs in one basket. We preserve plurality and we preserve greater privacy by having people's financial data hosted by private firms who are not required to turn it over to the government on a whim.

[00:18:23]So, you might ask what's the danger of providing a public option? What harm could that do? I have three main concerns. One is that it's wasteful, and there are two senses in which it's wasteful. One, the Fed doesn't know anything about providing retail payment services. They provide wholesale payment services. The Federal Government in general has a poor track record at providing consumer services. So I think it's pretty likely that the Fed would either provide these services at a higher cost than necessary and thereby lose money at taxpayer expenses, or it would just cut back on service. It would provide poor customer service.

[00:19:07]Evidence. The Central Bank of Ecuador launched a retail account system in 2015. But the project didn't attract users. It was poorly designed. It was poorly marketed. The public didn't trust the system, and it was terminated after two years. They pulled the plug on it because it was losing money. Second concern about efficiency is that bank deposits provide funding to banks for lending and under the Fed Accounts Model, if people move their retail transaction accounts, their checking accounts from commercial banks to the Fed, then they also move the funds that provide commercial bank loans. So it would shrink the volume of loans that banks can make, and it would substitute centralized allocation of those funds for decentralized competitive allocation. So that worries me. I consider that a bug and not a feature of the system.

[00:19:59]Second I'm concerned about innovation, right? We want a payment system that continually improves through innovation and in the private sector, as Bob acknowledged, we realize on innovative startups to introduce new technologies and to keep developing new products that consumers want, and that's what we've seen in recent years. I've mentioned Venmo, Cash App, in China there's Alipay and WeChat Pay. In India there's Paytm. In Kenya there's M-Pesa, which is a cell phone payment system and these kinds of private initiatives are remarkable they are improving people's lives. What have central banks done? Not a lot. It's not what they're cut out for. Central banks administer the wholesale payment system which is pretty much routine, nowadays. And third concern, which Bob mentioned, but seems to think that Central Bank Digital Currency is not a threat to, is privacy. But some designs, at least, track where every dollar goes. The Chinese government's digital currency model is built precisely for surveillance to track where every Yuan goes, and so that's an especially bad model for the US to emulate or to try to catch up with. Whereas Apple Pay encrypts customer data, so we have to worry about how to prevent the Fed from making that data available to other Federal Agencies that want it. I'm not saying that the Fed has any interest in giving it up, but they don't have much interest in stopping giving it up when the IRS comes calling or the DEA or the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms or Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. Today, those agencies has to go to commercial banks and commercial banks have some ability to resist this kind of information fishing. Although they put up actually too little resistance cause they have to worry about their licenses. But I can't see the Fed putting up any more resistance. So I worry that it erodes privacy, and I think therefore there's less danger of a financial panopticon, which I'm sure none of us want, where digital money balances are issued by a plurality of institutions whose customer data is not available to the authorities without permission or without a warrant. So let me stop there and we'll move to stage two.

The issue of privacy in adopting CBDC

[00:22:23] Richard: [00:22:23] Great. Great. Lots of great points from both sides. And, it's a little bit harder for me to keep track. But I'm sure that every point will get addressed in this debate later on. So let's move to round two and I'll be sending questions to both sides, and I'll start with Bob. So we did talk about privacy. Both sides did talk about privacy in your opening statements. It seems that there's some consensus in terms of the importance of privacy for the citizens, whoever essentially implements the payment system, a public option or a private option. But in the CBDC's case in the US, what is a good way for the government to ensure that the privacy is provably provided? So in China's case, for instance, I think that the promise is softly underwritten. The government just says, "Oh, don't worry about it". And in fact, I think that it's an open secret that that information has some kind of backdoor. And in fact, I think state surveillance is actually one of the very important goals. In fact, I'm actually not even surprised if a big part of the Chinese citizenry endorses that, embraces that in hopes of just harmonizing the society and fighting the bad actors. So the question to you Bob is, how do you think the state in the US can provably conclude that privacy of the citizens in using the payment system will be insured?

[00:23:58]Bob: [00:23:58] Great. Yeah. Wonderful question. And nicely resonates, I think with Larry's last set of points, which were quite compelling. I think maybe the best way to approach this is to ask ourselves, first of all, what the options would be. Second of all, what the potential threats to privacy might be, and from whom they might end up emanate. Then third, what are the incentives relatedly, and then fourth, what is the potential legal response? So to start with the first, note that if we think of a CBDC or of a Fed system of the kind that I'm envisaging and in the way that Larry characterized and I should have characterized as a public option, then of course, there's no requirement that people resort to that system. So if anybody is especially concerned about the possible compromising of their financial data or their commercial data by dent of using a Fed system, they could of course stay off of that system in the same way that they can refrain from using any particular private provider who they think or worry isn't going to be as sensitive to their privacy concerns as some other provider might be.

[00:25:03]Second thing to note, is that privacy for the most part, or at least privacy in substantial part, is itself a creature of law and legal protection, right? In other words, while there are some incentives to offer privacy on the part of private sector payment service providers right now, and private sector banks, there are also very strictly enforced laws that require that that privacy be protected. There's absolutely no reason you couldn't similarly or identically legally require the Fed to observe the same sorts of privacy standards or even higher privacy standards, if you wished to, right?

[00:25:43] Third then, if we ask ourselves what are the threats to privacy or at least what role do incentives play in compromising privacy? You might say that the Fed has at least, provisionally, more incentive to comply with law enforcement authorities immediately than might a private sector bank as Larry observed. But by the same token, you might imagine that a private sector banking institution or a private sector payment service provider has more incentive to listen to the blandishments of would be data harvesters who want to sell consumer data to marketers than the Fed has, right? So in other words, you've got temptations that emanate from different angles that are faced by both the private sector and the public sector when it comes to dealing with privacy. And it seems to me that we have at least as much reason to worry about private sector providers succumbing to the temptations put before them by data harvesters as the Fed has to succumb to demands of law enforcement. But either way, whatever the incentives might be and however powerful they might be, again, it's very straightforward simply to prohibit as a legal matter the provision of the kinds of data that are requested, no matter who's doing the requesting absent the provision or the supply of some kind of warrant, some sort of court order or basically some legal process determined authorization for that release of that information.

[00:27:06]Richard: [00:27:06] I think it's actually very compelling. I'm curious to hear, Larry's response.

[00:27:10]Larry: [00:27:10] I certainly agree with Bob that Central Bank Digital Currency, should it be offered, should be optional. Nobody should have to use that account. Commercial bank accounts should still be available, and cash should still be available, and that allays some of the privacy concerns about a financial panopticon no doubt, and I'm also in favor of requiring the Fed to obey privacy standards if they're in a position to have consumer data. I don't know of any scandals where banks have been disclosing personal information, but maybe Bob does. If that is a problem, then banks of course should be required to disclose their data harvesting practices so that their customers can make an informed decision. But as I said before my worry is not so much what we instruct the Fed it may do and may not do as what happens when those instructions come under stress. When the treasury comes forward and says we have this special case where we want to break the encryption on somebody's iPhone. They can come to the Fed and say, we have this special case where we want to break the privacy of this account because we have the following suspicions.

[00:28:22]Richard: [00:28:22] Although theoretically, they could go to a private entity offering a payment service to make that kind of special request too. Is that not the case, Larry?

[00:28:31]Larry: [00:28:31] Yeah and they do that but the private financial provider has some legal recourse. So under the current law, they have to give the customer notice when they're handing over data to the federal authorities and the customer is supposed to have at least a couple of days to try to stop it in court, to get an injunction. Not clear how that would work in the case of the Fed being requested to turn over data, but I suppose this same sort of safeguard could be put in place. I would like the bar to be higher, I would like a warrant to be required.

[00:29:06] Richard: [00:29:06] Okay. Bob, would you like to respond to that?

[00:29:08] Bob: [00:29:08] Yeah, I'm quite with Larry on that. It seems to me that a warrant should be required, I can't really see any particular reason not to hold the Fed to precisely the same standards, if not higher standards, to those to which we hold private sector banking institutions and payment service providers like PayPal, Venmo, and the like.

[00:29:25]Larry: [00:29:25] But you realize this is contrary to the whole know your customer anti-money laundering emphasis of the US treasury?

[00:29:32] Bob: [00:29:32] I get that. But this is actually one case where I think the Fed's nominal independence from the treasury is probably something worth celebrating. There are of course other respects in which partial independence is worth celebrating too. But here's one where, again, there's no reason that we can't hold the Fed to precisely the same standard that we hold private sector banking institutions, irrespective of the demands or the tantrums that might be thrown by anybody over at treasury.

Practicality of setting up a CBDC

[00:30:00] Richard: [00:30:00] Okay. So can we talk about the practicality of setting up a CBDC at the moment? So there are a few different angles to understand this. I think that the treasuring of personal privacy, especially financial privacy in this country, it's certainly a lot higher than in a place like China for instance. There just seems to be at least in recent years a surge in terms of distrust for institutions, both public and private, but especially for the public. So if the policy makers try to push the agenda of coming up with CBDC, what do you think are some practical impediments? Also, why do you think that the momentum of trying to implement this plan has been so slow? And I think this question is probably better suited for Bob, but Larry, feel free to jump in as well.

[00:30:51] Bob: [00:30:51] Yeah, I'll answer really briefly. And then I'm sure Larry will have great thoughts and response. So maybe the easiest way for me to address the question is by providing you more specifics as to what I myself have been proposing for some time now. And this will actually help address in addition of one of the first points that Larry made, which is that you do have to get a bit more specific about the particular modalities before whether to be in favor of a particular proposal or against one. So in my view, the easiest way to proceed is to start with the system of TreasuryDirect accounts that already exists. So some of your listeners or viewers, Richard might be surprised to know, it's surprising that it's surprising given how long this has been available, that anybody who's listening or watching right now can go to the TreasuryDirect website and open an account with the treasury department right now. Out of which one can purchase various treasury issued securities and into which one can redeem various treasury issued securities. All that's required is a social security number or some comparable sort of identification on the one hand and then a separate bank account in which you can hold dollars because you can't pull dollars and TreasuryDirect accounts on the other hand.

[00:32:03] So what I thought is the easiest way to proceed would be simply to start with TreasuryDirect and simply add the following basic features. First, allow TreasuryDirect accounts to hold federal reserve notes in addition to treasury notes or dollar bills so to speak, in addition to treasury bills, basically Fed instruments in addition to treasury instruments, and then also convert each account into not only a sort of vertical relation between the person on the one hand and the treasury department on the other, but also to allow for horizontal P2P interoperability between accounts on the part of all citizens, legal residents and businesses in the country. So basically convert TDAs into TDWs, right? Treasury Direct Wallets, and just start that way. You might also then say, okay, we'll limit the total amount that can be held in an account of this sort to $1,000, $2,000, maybe $3,000, so as to minimize the impact on the private sector banking system, at least at the front end, and keep it then therefore fairly minimal.

[00:33:12]Then over time, you can gradually integrate this into the full apparatus of Fed monetary policy, and in doing that kind of partly recapitulate the history of the paper dollar. Which began as private sector, privately issued back notes before the mid 1860s. Then supplemented and edged out by a privately issued greenback currency that was administered by a regulator within treasury tellingly called the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, whose name only makes sense against the backdrop of that history but nobody seems to understand what it means now because we don't treat the treasury or OCC that way. But in any event, basically recapitulate in a kind of updated form in the digital space, something like the history of the treasury dollar of the mid-1860s, ultimately supplanted 50 years later with the coming of the Federal Reserve backed by a Fed administered central bank issued and managed dollar.

Motivation for the right and left to implement CBDC

[00:34:06]Final point in this connection, I started pushing this under the rubric of essentially what I call digital greenbacks because the first treasury dollar was called the Greenback, about a year and a half ago, and talked to quite a few Congress members about it and got some enthusiasm about it from Democrats and Republicans alike. Republicans are more excited by the China angle. Democrats are more excited by the financial inclusion angle, but basically all seem to be excited. But one thing, one final point that sort of helps get them excited was that I first contacted US Digital Service, which is sort of a relatively new tech oriented department within the Federal Executive that was put in place during the Obama years. It's said to be a kind of personal favor to Vice President Harris. But I talked to USDS and asked how long would it take to do the conversion of TreasuryDirect into this kind of provisional digital greenbacks system, which then might ultimately be grown into a full Fed administered digital dollar and they said, at least as far as that, the sort of initial changes, the sort of wallet conversions and the universalization of the wallet availability is concerned, that would just take a few months. That that could be, I talked to them, I think it was in March of 2020 and they said by the end of the summer 2020, this could be more or less operational. I am assuming that they would say more or less the same thing now.

[00:35:22] Richard: [00:35:22] Okay. I mean, it sounds like from a technical perspective, the implementation is not all that difficult . I think it's the, somehow the political will or just a matter of priorities for the policymakers, but what's holding them back? It sounds like there is some kind of consensus across the aisle. He's mentioned the China angle for those that lean right and then the financial inclusion angle for those that lean left.

[00:35:45] Bob: [00:35:45] I'm guessing the main reason is something that, Larry would probably agree with. And it might be surprising that I agree with Larry on this. And that is that the private sector offerings right now are pretty good. There's not a great deal of urgent need...

[00:35:56] Larry: [00:35:56] Yes.

Using the Fed to achieve universal availability and universal interfacing

[00:35:57] Bob: [00:35:57] of conversion. The way I view this as this would be an optimization of what we already have and again, this in a sense what we would be talking about here is a very familiar sort of evolutionary term. Consider the Federal Reserve System itself, for example. It began as a sort of universalization of a kind of liquidity risk pooling arrangement that had already been privately determined or privately developed and privately ordered in a less perfect way you might say in the old clearing house system. So the New York clearing house system that had a lot of member banks, pooled liquidity risk together. There were various other clearing houses all over the country. The New York clearing house seems to have been the best or the most effectively operating one. But the others did less well, but still more or less satisfactorily. But the crisis of '07 and developments subsequent to that got federal legislators on both sides of the aisle again, interestingly enough and both private sector bankers like Paul Warburg on the one hand and more public sector oriented folk like Carter Glass of Virginia on the other hand to think we might optimize this system if we were to universalize the risk pool, and this is just the logic of insurance, right? Simple scale economies of insurance.

[00:37:10] And so in effect what they did is they socialized the New York Clearing House arrangement. At least as far as liquidity risk pooling was concerned. And we now had a kind of national clearing house for any bank that wanted to be a member. And you weren't required to be a member of the Federal Reserve System. You were, if you wanted the Federal Banking Charter, but you could still seek the State Banking Charter, and one way of looking at what I'm suggesting right now, is that this would be a similar move, right? We just say, all right look, the private sector has developed some pretty good modalities here, payment modalities, so has TreasuryDirect for that matter, although it's got a much more limited purpose. Why don't we just make this kind of universally available, even if not universally required and meanwhile allow continued evolution and development to occur in the private sector here and bring in more of those bells and whistles into the public system, if the private sector develops them, and the private sector, if it's as innovative as, Larry suggests, and I think most of the time or very often it is, they will always be a little bit ahead when it comes to the bells and whistles, but it will be a little bit behind when it comes to universal availability and universal interfacing. And so we can have, in a sense, the best of both worlds. If we have a public system that continually improves in the light of private sector developments, that covers the sort of universality and interfacing basis better than the private sector does, while we still have a very vibrant private sector out there continuing to develop new innovations when it comes to what I call bells and whistles before.

[00:38:36] Richard: [00:38:36] Okay. Larry, would you like to respond to that?

Monetary History and why going back to Greenbacks is a bad idea

[00:38:39] Larry: [00:38:39] We're getting a little bit deep into the weeds of monetary history. I hope listeners don't mind that, but, this is my specialty, so I have to respond to that. This is the first time I've ever heard the Greenbacks cited as a favorable precedent in monetary innovation, right? The Greenbacks were a wartime measure to finance the union war effort. And they were issued by the treasury, and were not redeemable into gold, so that's what made them of source of new finance. It was an alternative to borrowing the money on the international bond market, was just printing up paper dollars. They were not redeemable into gold so the US had to go off the gold standard for the duration of the war. There is a great deal of inflation and only 15 years later was the price level back down to normal to the point where redeemability of the Greenbacks could be re-established.

[00:39:36] A second war time measure in the Civil War was the National Banking Act, which created the federal charters that Bob referred to and with the national banks that the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency was responsible for because those banks issued currency, and that was not a natural development. The federal bank charters, and especially not the prohibitive tax on bank notes issued by state banks. That's very much steered by legislation for war finance reasons, not for optimizing the payment system. Now the national banking system was notoriously inelastic in supplying currency because the bond collateral that was required to back the notes to issue notes, you had to buy a union government debt, and there was only a certain amount of it that was eligible.

[00:40:27]The quantity of currency couldn't expand seasonally or cyclically to satisfy increases in the demand to hold money, that led to the financial panics, and that led to well, two reform proposals. One was people noticed that Canada didn't have these restrictions on banks, had no panics, so why don't we have a more competitive, a more free banking system the way Canada does? That was killed by the small bank lobby who said, but Canada has nationwide branch banking. We don't want New York and California banks branching into our turf, they supported some kind of measure which would make them able to compete. Namely, keep the large banks out but instead create a Federal Reserve System. So in my mind that was not a natural evolution but actually a second best reform that was adopted for political reasons. After the panic of 1907, as mentioned when the New York banks went from opposing a federal institution to saying it's okay with us as long as we can control it.

[00:41:32]So that's the evolution of the Fed, and as Bob indicated, there was already a perfectly suitable, interbank clearing system provided by clearing house associations in the major cities and the city where the clearing house of Chicago and the clearing house of St. Louis and Pittsburgh and so on all cleared was in New York, so that was the sort of central reserve city of the system. That was to some extent artificial because of the ban on branch banking. Banks in Chicago could not open their own offices in New York City, but New York City was the financial capital, so they had inner bank deposits and it worked through a correspondent banking system. But I wouldn't regard that as a model of how to evolve the banking system. It had a lot more problems than the more naturally evolved system, which was the Canadian system at the time.

[00:42:23]So likewise, I don't see moving digital payments from private sector providers to the Fed is any kind of natural evolution. You can think of it as a kind of public option or an add on, and as long as there are privacy protections, and as long as nobody's coerced into it, as long as cash is still available, as long as cryptocurrency is still available. So the only people in the system are those who think it has some advantages, that would minimize the objections I have to it. But then it would just be a question of, are people willing to pay for it? Is it worth the cost? Because neither the treasury, nor the Fed has any experience in providing customer service.

The role of cryprocurrencies in CBDC, dollarization and thoughts on countries adopting Bitcoin as a legal tender

[00:43:10]Richard: [00:43:10] Okay. So Larry, just to latch onto that last point. You had mentioned that this is not necessarily something urgent, CBDC is something possibly nice to have, but who knows how much it will cost and weather the benefits will outweigh the costs? What do you think are the existing solutions that are working so well outside of Zelle and outside of the other traditional solutions you have mentioned? For instance, what are your views on things like stablecoins and what are your views on cryptocurrency as playing a role in facilitating payments?

[00:43:45]Larry: [00:43:45] I don't expect stablecoins or cryptocurrencies to play a big role in payments. We're on a dollar system. People are not going to abandon the dollar for Bitcoin as a medium of exchange, as a medium of exchange in their checking accounts. They've got rent due at the end of the week. People want something that has a stable value in terms of the rent contract. So if the rent is in dollars, people want to hold dollars, not Bitcoin. It's risky to hold Bitcoin. Can drop 10% in a day. Now stablecoins are a little more interesting because they are denominated in dollars. At least dollar stablecoins are denominated in dollars. But where they're currently being used for payments is in cryptocurrency markets.

[00:44:29] So people acquire Tether when they sell Bitcoin and then they use it to buy Ether or vice versa. Now people used to use Bitcoin for that role, but the volume of stablecoins has grown enormously, it's over a hundred billion now, and so people seem to find it more useful because it's a more stable medium of exchange. It's got more stable purchasing power. But those are large dollar payments typically. I'd be reluctant to hold much of my checking money in stablecoins because really they're only accepted in cryptocurrency markets. I can't spend them at the grocery store and they're providing a service of just parallel to what banks provide for ordinary consumers. You have to be careful if you're deciding where to park your money in the cryptocurrency market, to look for a stablecoin issuer that has some transparency about what reserve assets it's holding to back it's dollar denominated claims. I'm hoping that competition for users will compel the stable coin issuers to be more transparent than they have been so far. But I think they're currently caught between a rock and a hard place, because if they were to actually provide enforceable redemption contracts, then they would become banks. They would be legally banks and they don't want that because their customers don't want that. Their customers don't want to be subject to know your customer regulations and other bank restrictions that would drive away their customers, so they've remarkably held their value. That's an impressive thing about them. Tether, USDC, PAX, Gemini -they've remained pretty close to their dollar pegs, pretty much within the range of 0.98 to $1.02.

[00:46:18] There are other stablecoins that supposedly maintain the peg by an algorithm rather than by backing, but I don't really understand how they work and some of those have been known to break down. There are others that haven't yet broken down, but I'm not sure how they've managed not to break down yet, maybe they just haven't been under much stress yet. So stablecoins have a role in cryptocurrency markets, but it's hard to see them, their role being broadened very much beyond that. They do have a role in spreading dollarization to countries with really bad currencies. So if you want to keep your savings in dollars, but a US bank account is not available to you because you're in Venezuela or you're in Lebanon or you're , god forbid, in Iran, where sanctions prevent you from doing dollar business. They provide a kind of access to dollar denominated assets.

[00:47:18] Richard: [00:47:18] Okay, so it's interesting you mentioned dollarization in other countries. Over the weekend, another country in North America, the smallest country El Salvador, actually mentioned potentially adopting Bitcoin as it's legal tender . Announcement by the president into the Miami conference.

[00:47:36] Larry: [00:47:36] I, don't think correct me if I'm wrong, but I don't think he announced that they were going to switch from the dollar to Salvador's currently on the dollar standard.

[00:47:46] Richard: [00:47:46] I think it's another

[00:47:47] Larry: [00:47:47] But it would be a legal tender. It would

[00:47:50] Bob: [00:47:50] yes,

[00:47:51] Larry: [00:47:51] be the contracts in Bitcoins. It would be enforceable.

[00:47:55] Richard: [00:47:55] Correct. So would be an additional legal tender. So if a citizen that country were to try to extinguish their debt with Bitcoin, then the person lending the money can't say, no we don't accept it. That's my understanding of what people can do.

[00:48:09]Larry: [00:48:09] It should be that if the debt is denominated in Bitcoin, that it can be discharged with Bitcoin. It shouldn't be that if the debt is in dollars, you can switch to denominating it in Bitcoin without the agreement of the other side.

[00:48:21] Richard: [00:48:21] What about products and services? So if I run a grocery store in El Salvador and I quote my apples in dollars, if someone goes in and says, I only pay by Bitcoin and the grocer, can they refuse?

[00:48:34]Bob: [00:48:34] It really depends on the nature of their legal tender loans. Larry, in effect invoked an important distinction here, right? Legal tender is understood legally here in the US to mean, basically you can discharge debt obligations but that doesn't necessarily mean spot transactions. If it does include or entail spot transactions in El Salvador, then people would have to accept it point at the store as well. I would be surprised, however, if that's what El Salvador has in mind.

[00:48:58] Larry: [00:48:58] But it would be legal. I think this is the intention. It would be legal for a merchant to put up a sign saying we accept Bitcoin. Whereas in some countries that's not legal.

[00:49:06] Richard: [00:49:06] Okay. What do you think is the true intention behind this announcement? What is your read?

[00:49:12] Larry: [00:49:12] Well, since El Salvador is run by a kind of strong man, I think he's looking for some positive PR. I think it's a public relations announcement.

[00:49:22] Bob: [00:49:22] Yeah, that makes sense to me. Probably the same reason that Manny Pacquiao announced he was going to issue a PAC coin a couple of years ago. It's not clear what a boxer or a great boxer or indeed a legendary boxer has for this other than maybe a kind of a marketing thing. Not unlike maybe Bowie bonds of the kind David Bowie announced he was going to issue like 30 years ago or something. It's a way of getting in on a fad that is occurring in the financial markets, and in Bowie's day, the big bang had occurred in London and the financial markets were really taking off, and so it looked like an innovative thing to do. It's an innovative performance artists to say "I'm going to issue bonds, where people can invest in my own future extravaganza shows", and the like. Manny was probably thinking something similar when it came to promoting his own bouts a few years ago, and as Larry suggests, I wouldn't be surprised if the head of El Salvador is basically capitalizing on or riding a wave of enthusiasm and faddish excitement about the crypto space these days.

[00:50:21] Larry: [00:50:21] No, I, it might be more positive if he said we're going to be open to Bitcoin businesses. It might be that his intention is to bring in Bitcoin financial services to relocate to provide white collar jobs the way the Grand Caymans is an off shore banking center. But then as a business, that's thinking of relocating to El Salvador, you have to ask yourself how durable is this commitment given that it's issued by this strong man ruler and not by the legislature?

Hype vs reality: The possibility of China's CBDC becoming a currency to settle international trade and therefore be a real threat to USD

[00:50:57] Richard: [00:50:57] Got it. Okay. So while we're talking about international markets let's reel back a little bit and talk about the China CBDC. It was mentioned earlier during the debate that there are those that worry about the China CBDC's influence and potential in toppling USD as a world reserve currency. So this question is for both of you. What do you think is hype versus reality when it comes to the possibility of China's CBDC essentially becoming a currency to settle international trade and therefore be a real threat to USD?

[00:51:33] Bob: [00:51:33] I think it's largely hype, in one respect and less hype in another. The respect in which I think it's largely hype is that people seem to be overlooking or forgetting the fact that China's growth model still remains largely export led, right? There's a lot of noise that they make about trying to transfer their reliance more to domestic consumption and domestic growth, and that's happening to a considerable degree as well. But it remains the case, I think that China for a long time to come wants to have an exporting edge, and having reserve currency status is quite inimical to that particular ambition. So my own guess is that China is very happy to see the dollar continue to function as a defacto global reserve currency for a good long time to come.

[00:52:14] And so I doubt that a digital RMB is aimed at supplanting at in that way. That being said, I can imagine that what we know, we have it on record that China very much wants to dominate new information technologies, new encryption technologies, all sorts of new technologies in the coming decades, and it is thought that the cryptocurrency space is a space where a lot of that innovating is happening. Not we're all of it is happening and probably even a diminishing proportion of the total is happening in that space, but it nevertheless remains a very conspicuous piece of that general zone, you might say, in which rapid development is underway, and so China probably has a great deal of interest in being involved in crypto developments pursuant to that other ambition. That would be my guess.

[00:53:03] Richard: [00:53:03] Okay, How about you, Larry?

[00:53:05]Larry: [00:53:05] Bob said something interesting earlier, which is when he's been pitching Central Bank Digital Currency to Congress, some Republicans jumped on the argument that, oh, China's doing it well, we don't want to fall behind China. So that's a kind of hype. I don't think this has much to do with international trade, right? Where the dollar is the dominant unit of account and medium of exchange and large value international trade payments are already being made at digital dollars. Doing it electronically or online, that's not an issue. The Chinese CBDC is a retail system. It's a payment card. It's a phone app. That's not what's going on in international markets. That's not the kind of payment people want to make.

[00:53:52] Secondly, I believe this is right. To use it, you have to have an account at one of China's government owned commercial banks and then you have to identify yourself when you use it so the Chinese government can track all your transactions. So people in other countries, global business-to-business business transactors, they're not the target clientele. It's Chinese retail users that are the target clientele. And I agree with Bob, China, as long as the Yuan is not a freely convertible currency, as long as China has exchange controls, it's not going to be a international currency of choice. The dollar has an established network, it's a network good to use the same money that your trading partners are using. It's hard to crack that open unless the incumbent currency gets really bad. As long as the dollar maintains a reasonable, a low inflation rate and inflation rate comparable to that of other major currencies, other major currencies are going to have a hard time taking that business away.

[00:54:56] Now, there is one threat to the US dominance that I want to mention is that, which just that the US government has been using sanctions on banks doing dollar business with disfavored foreigners, and that makes people reluctant to put their money in dollars because they might be next. So provided that that doesn't get out of hand, I expect the dollar to continue as the dominant international currency.

Sanctions and freezing of USD assets

[00:55:22] Richard: [00:55:22] I have a curiosity. If someone were to have USD assets and subsequently got sanctioned by the US government for whatever reason, why can't that person subsequently convert that dollar to something else? Is it because the USD accounts are somehow tracked by the government and can be frozen at a moment's notice?

[00:55:40] Larry: [00:55:40] Yup. Yeah, so Iranian accounts in New York banks were frozen.

[00:55:44] Bob: [00:55:44] There's also even beyond that, of course, if the US has particular sort of reciprocal arrangement with other jurisdictions, they can seize assets in other jurisdictions as well if people try to in effect exit the US and shelter themselves elsewhere. That's in turn, of course, part of the reason for the growth of certain financial centers off shore that don't have those arrangements with the US. Because that's what it takes to function as a shelter. It's basically not to have an arrangement of that kind with US authorities.

The key word: Urgency

[00:56:15] Richard: [00:56:15] Okay. So we've been talking a lot about the benefits and disadvantages of having the CBDC, but let's touch upon the keyword of urgency here. So I remember in 2020 when the CARES Act was passed and these checks were being made to Americans in support of their livelihood during COVID. I think there was a provision about potentially setting up some kind of digital dollar. I think it was printing of two $1 trillion coins or something like that embedded in one of the bills. I don't know if that suggesting eventually became built or not. But I think it was sponsored by one of the politicians in The Squad. And there was a gentleman named Roland Gray that was very much behind this whole effort. Rashid Tlaib. So I think the argument made at the time was that I think there was a lot of urgency in terms of reforming the way in which the government pays it's people . There were checks being mailed to the wrong address that were not cashed. They were lost in the mail and so on and so forth. So from that particular angle, in terms of reforming the system to provide a more efficient helicopter cash system, if you will, can you talk a little bit about why this is urgent?

[00:57:30] Bob: [00:57:30] Yeah, a couple of things here. So first the coin proposal, I think, has to be severed from the universal accounts proposal. They're in effect, are about different things and they are motivated by different iterations. The trillion dollar coin proposal originated with Carlos Mucha, who's a very distinguished and brilliant lawyer here in the US. He was blogging for a time back in 2008, 2009 under the name of Beowulf. And he proposed the coin proposal basically as a workaround to get around a then-austerian Congress that was making noises about not raising the debt ceiling. So the question was, can we get enough congressional appropriations to do the kind of public spending that's necessary to avoid a deep recession after the 2008 crash?

[00:58:19] And so what Carlos pointed out was there's a provision in the legislation around the mint having to do with commemorative coins that sort of through a kind of oversight failed to impose any obvious restrictions on the dollar denomination that can be attached to a so-called commemorative coin. So in a kind of whimsical moment, but he was also serious because the circumstance in 2009 was pretty urgent looking. Carlos said we should just seize upon that particular loophole and a statutory provision that really has nothing to do with public finance, it's just about the minting of commemorative coins, seize upon that loophole and just designate a particular coin as being worth a trillion and then deposit it in the treasuries account at the Fed and voilà , we have another trillion dollars to work with not withstanding Congress's refusal to appropriate funds.

[00:59:10] Now I myself was skeptical at that time for a number of reasons, but the main one was that there was a way of basically dealing with the debt ceiling problem. That didn't involve any kind of gimmickry like misusing a particular statutory provision for a purpose that it was never intended for. So I was against it, but at least I had a place there. You can see the logic to it. The oddity about re-resurrecting the coin proposal I fought in 2020 was that there wasn't a problem with an austerian Congress refusing to make appropriations. It basically said do whatever it takes. You had both Mnuchin and Powell agreeing look let's just appropriate and spend and do whatever we gotta do right now to deal with. Also, there was no shortage or no a deuced shortage of public demands available. So it didn't make sense. It seemed to me to be trotting it out again now, even less sense than it did back in 2009. On the other hand, what did make sense? And this is an effort that I was behind and I think a number of others were as well, to say, look if we want to get these payments, these CARES payments out quickly to people. And if as was widely believed mistakenly, it turns out in retrospect, but as if as was widely believed at the time paper like paper checks was a vector of the virus itself. A lot of people seem to believe that at the time, myself included, then it's very urgent that we enable the treasury to make money available to people by electronic means rather than sending them checks that might reach them, might not. And then require them to wait on long queues over at check cashing centers in inner city areas where they're going to communicate the virus or catch the virus waiting to cash their checks. And then have, I don't know, 10 or 15% docked from it by the cashing entity. Now what's happened since then is it's emerged paper is not a vector for one thing. Furthermore, God bless them, PayPal, Venmo, and other private sector payments services, volunteered basically opened accounts for people who would receive treasury payments. So the payments could be made right into PayPal accounts and the like. And so a lot of the urgency, I think that we seemed to be confronted with, or at least I agreed and we were confronted with back in the spring of 2020, and that's one reason I'm speaking more in terms of optimization and convenience now, rather than in terms of urgency as I was about a year and a half ago.

[01:01:26] Richard: [01:01:26] Okay. By the way. So is it true that now you can receive US treasury assistance through a PayPal account?

[01:01:33] Bob: [01:01:33] I don't know whether that's still operative, but it was, I think in the summer that did become operative for at least a while, but I'm not, I haven't followed through, I on that to see if that's so. Partly because of course, the payments are set to expire by the end of the summer. So I haven't been following where we are on that right now. But maybe actually Larry is more up to date on that.

[01:01:55]Larry: [01:01:55] So what I'm hearing is that CBDC is not as urgent as we once thought.

[01:02:00] Bob: [01:02:00] Yeah, no, this is what I'm trying to say throughout is I think this is a matter of optimization and universalization.

[01:02:06] Larry: [01:02:06] I would agree with that.

[01:02:07] Bob: [01:02:07] I don't think it's a matter of urgency, at least in the same sense that I thought it was in the spring of 2020,

[01:02:15] Larry: [01:02:15] Okay. So then I think our basic disagreement then is, is this a destination that we want to head toward? Not the speed with

[01:02:21] Bob: [01:02:21] yep.

[01:02:22] Larry: [01:02:22] which we head toward it?

The Federal Reserve Act and comparison with other banking systems

[01:02:24] Bob: [01:02:24] Yeah. Although I think, speed is easy to do if we're talking about starting small through the TreasuryDirect conversion that I talked about before. And so in that respect, I would very much be in favor of speed. I would like to see this done by the autumn. By this, the TDA conversion to treasury offered wallets. This is a nice point of entry to make a quick observation about the greenbacks, that we both mentioned, Larry. It's true that there were difficulties with the greenback and it's true also that one of them was, it was very hard to modulate the money supply when the money supply was greenbacks, which is precisely one of the reasons that we decided to add a central bank to our fundamental and our portfolio of fundamental institutions of public finance. Because that's of course, what central banks do is they modulate supplies. Right? The idea is precisely to curtail the supply when things are overheating and to expand the supply when things are slowing down. And the treasury department wasn't good at that.

[01:03:23] Larry: [01:03:23] Yeah. My point was that the Canadian system did that quite well without a central bank.

[01:03:27] Bob: [01:03:27] Yeah, and that's just, one hears a lot about the Canadian system and the Australian system as well and how they work a lot better than ours with a much different sort of regulatory footprint. There are problems that I think it would become tedious to get into in our remaining time with those comparisons, of course, because you can't look at central banks or finance ministries or ex checkers, or what have you, in institutional isolation. There are additional sort of legal regimes that all interact and present us with a kind of mosaic that basically amounts to our financial system with our banking system as being a part. And what I'll do I suppose is suggest that some of our listeners and viewers might want to Google Canadian banking system or Australian banking system or comparisons between the two to get a feel for where the sort of comparisons break down and where there are ups. There are various theories or conjectures that are offered, especially by my Canadian finance regulatory friends, as to why the Canadian system might not actually be transportable to the US. It might not be importable. But from my point of view, that's an open question, right? That is certainly open to debate. I don't want to be dogmatically dismissive of the comparison. I just want to introduce the caution that the comparison can't be blithely made without looking at other components of financial system and the financial regulatory system.

[01:04:52] Larry: [01:04:52] Okay. And then our debate today is not about the re-litigating the Federal Reserve Act.

[01:04:57] Bob: [01:04:57] Bingo. Yeah.

[01:04:58] Larry: [01:04:58] It's about where we go from here.

[01:05:00] Bob: [01:05:00] Right.

Reactions on cannibalization of business from the public sector into the private sector

[01:05:01] Richard: [01:05:01] Right. And Larry, here's an audience question for you. We haven't talked about how the CBDC would affect the operation of private commercial banks. So some worry that there will be some kind of cannibalization of business from the public sector into the private sector. What are your thoughts there? What are ways to reduce adverse impact on these banks, if any, and what are some ways to reduce the negative second order effects from the damage to banks? So talk about how there will be some kind of negative effect to private banks, if any, and then what are some ways to resolve those problems?

[01:05:36] Larry: [01:05:36] Yeah. It's a good question. I mentioned this briefly, but let me go into a little more detail. If people move there to the extent that people move their money from commercial bank accounts to a Fed account, then the banks shrink. The banks don't have as many funds to lend out. So the system we rely upon for financing small business gets undermined. Banks have less money to lend. And they're the experts in our system in figuring out who is a credit worthy borrower and who isn't. Which small businesses have a viable business plan and which ones don't. That's the job of bank loan officers. If we move that money to the Fed, then the Fed has to make that decision. They have no expertise at making those kinds of decisions. And let alone the incompetence red tape, the fiasco that was the main street lending program that the Fed and treasury tried to mount last year. They were unable to come to a set of criteria for choosing the worthy borrowers and very, very little was lent. But this is not just a one-time thing, this is a permanent effect. If we shrink the commercial banking system then we get fewer loanable funds available to business borrowers, and that's who we rely upon for innovative businesses, right? A lot of employment is in small businesses and so on. So we need a vibrant small business sector.

[01:07:05] Now, one proposal for dealing with that problem by some economists, who've recognized that it's a problem is to have the Fed lend the money back to the banks. So have a big auction where instead of banks gathering deposits, and then deciding how to lend them, the Fed gathers the deposits, they sell the money to the banks, and now the banks go back to deciding how to lend it out. And I worry that one, it creates a needless additional step, but more importantly, that the Fed that is going to have other agendas placed upon it as to who are worthy borrowers and who aren't, right. Just Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac did. Just the commercial banks have through various kinds of regulations. And so I worry about the politicization of the intermediation process, even if the Fed lends all the money back to the banking system.

[01:08:01] Bob: [01:08:01] Richard, can I say a couple things on this? Because my own proposal when we talk about getting beyond the initial front end, the sort of treasury administering of the plan, does involve of course migration of the plan ultimately to the Fed. And so I've had to confront precisely these questions. I think, that Larry was alluding to Jeremy Stein's observations about the Fed lending the money back to the private sector.

[01:08:24] Larry: [01:08:24] Bordo and Levin is what I had in mind.

[01:08:26]Bob: [01:08:26] Okay. So Jeremy Stein has also written extensively on this. And I think he has a somewhat less circuitous way of dealing with the problem that I think is by and large friendly to my own way of doing this. So what I'm going to do is first encourage your listeners or viewers to Google the phrase, "Spread The Fed" and my name. I've got a bunch of proposals under this general rubric of spreading the Fed. Basic ideas to go back to something like the Federal Reserve System that we had before the banking act of 1935. The idea here is that the regional federal reserve banks originally played a critical role as in affect regional development finance institutions. So the lead role was taken by private sector banks when it came to determining who was credit worthy, right? What small businesses needed development capital and the like. But they were able to lend a great deal more in this way if they could sell on to the regional federal reserve banks the commercial paper that was associated with the loans that were made to the small businesses.

[01:09:30] So a big part of the role of the Fed during its first 22 years of existence was to monetize commercial paper. But of course certain eligibility criteria had to be met. And furthermore, the regional federal reserve banks were actually designed specifically to be more regional economy responsive to have a better idea as to what was worthy of discounting and what was not. Which is just another way of saying what was worthy of Fed lending or lending assistance to and what was not. Now my own view is that the failure of the main street lending programs that were run out of the Boston Fed, and the municipal liquidity facility that was run out of the New York Fed was precisely the fact... There was more than one problem. But one of the most conspicuous problems of both was precisely the fact that they were run out of individual single, regional federal reserve banks, rather than out of all of the regional federal reserve banks with the Boston Fed looking at New England businesses, not nationwide businesses. With New York looking at New York municipalities and New Jersey municipalities, but not Peoria. And let the Chicago Fed the St. Louis Fed the San Francisco Fed and so on administer both programs for their respective regions. One thing that I've been proposing then is that we basically generalize from the lesson that we can learn from MLP and from MSLP, and spread the Fed again in a manner that's again, more consonant with what it was before 1935.

[01:10:58] Now, in that connection, if we do that, that offers a means of dealing with the possible disintermediation problem that is raised in connection with Fed accounts, right? What if people are depositing more in the Fed than in private sector banks? It's pretty straight forward. Basically private sector deposits on the liability side of private sector bank balance sheets would simply be replaced by discount lending from the Fed. And the Fed would not have to be particularly draconian in determining what's eligible or whatever. It could simply continue to outsource with a certain amount of deference, the initial lending decisions to the private sector banks. Just as it did before 1935 and simply impose certain minimal eligibility requirements that sound either in the minimal requirements that they impose now, or that maybe sound more in the requirements that we used before 1935. Which interestingly sounded not only in profitability, but they added one additional component which was productivity. And basically the Fed used an index of production that was developed by the War Industries Board during the first world war to help determine what looks like productive lending as distinguished from merely profitable lending. The idea being to try to screen out purely speculative lending.